As a creative practitioner, the foundation of your business is the imagination and vision which drives your artistry. Its success may depend on your ability to protect your creative output from being copied or used without your permission. The area of law which explains how to prevent this happening is Intellectual Property (IP). This blog will show how IP affects my practice as a photographer but will also help you relate IP to your own practice.Simply put, Intellectual Property Law prevents others from stealing your work and profiting from it. It takes two forms; statutory (acts of law) and common law. Which you use will depend on your field of business, however, your ideas are only protected if they are written down, recorded or made into something. They cannot be attributed and protected if they have only ever stayed in your head!

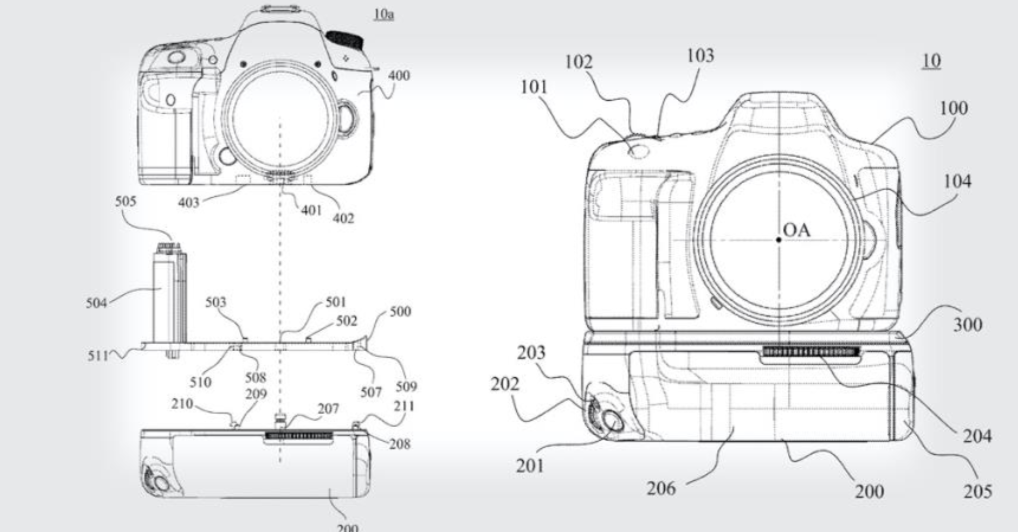

Patents, trade-marks and registered designs are statutory rights. To obtain these you must be proactive and gain registration. If you have created something new and inventive which can be made, then you should apply for a patent from the UK Patent Office. This gives protection in the UK; separate cover must be applied for in each country where the product might be produced or sold. To fit the ‘new’ criteria, applications must be filed before the invention has been disclosed anywhere in the world.

EXAMPLE: Canon Universal Battery Grip Patent

(US Patent Filed 30th August 2019) Published 5th March 2020)

https://www.newsgroove.co.uk/canon-patents-universal-battery-grip-that-would-fit- multiple-camera-bodies/

Trade marks (TM) are your unique business identity. By registering your trade mark, you will have the power to protect your brand and its reputation from counterfeiting. Your trade mark is your ‘badge’ and can comprise any element that can be represented graphically. There are certain things it can’t include (e.g. offensive language) and it must not be objected to by holders of registered trade marks, before being accepted and placed on the register. The renewable registration (via UK Intellectual Property Office) can be made in different product categories but only gives protection nationally and applications must be made in each country that you want to trade in.

If you decide against registration the common law of passing-off will give some protection. It is intended to prevent other businesses from masquerading as a well-known brand and profiting from that by confusing the public. This would damage the image or reputation of your brand in the public’s eye (goodwill). The protection it gives is limited by this goodwill and overall, it is considered to be difficult to enforce.

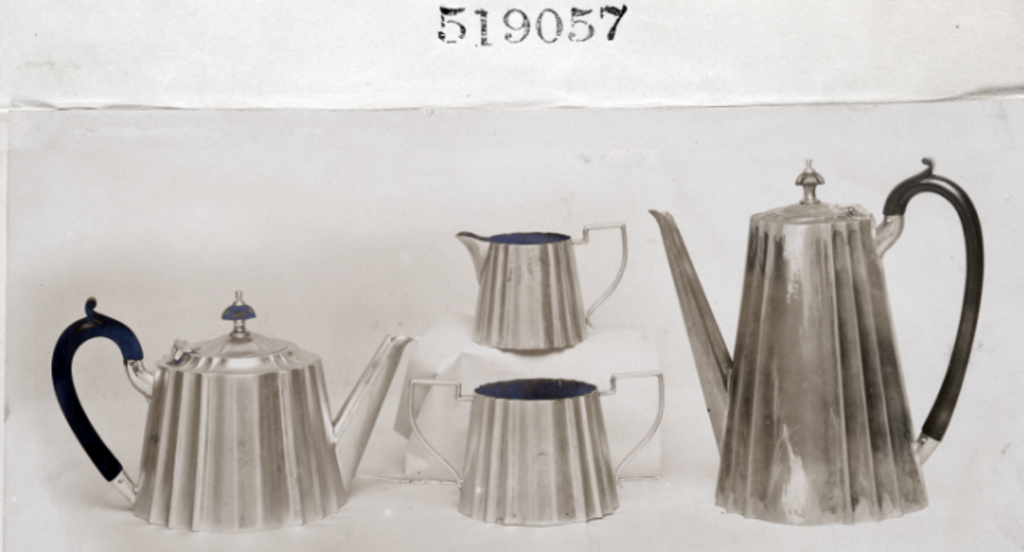

If design is part of your creative practice, for a fee you can protect your output by applying for Registered Design ® status. This renewable registration protects 3-D shapes and 2-D patterns which are new and have “individual character” in the UK only. Application is also through UKIPO (UK Intellectual Property Office) but unlike trade-marks the process is quick and easy. Registration will protect a product’s aesthetic; you cannot register a design for a functional feature, or where the appearance isn’t important to the buyer e.g., a car exhaust.

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/registered-designs-1839-1991/

Common law provides limited cover for a limited time against the copying of designs through “unregistered design rights”. Many have found that relying on this protection alone is an insufficient deterrent to design theft; ACID, a not- for-profit organisation, funded by membership fees, helps designers in the UK take a proactive stance to protect their IP.

The most common unregistered right is copyright. © It protects the economic and moral rights to a vast amount of creative output including literacy, music, drama, web content, software and visual arts. To qualify, work must be original and demonstrate a “sufficient level of skill, labour and judgement”. Copyright exists automatically from the point of creation and belongs to the creator. So, as a freelance photographer, I hold copyright to and therefore ownership of my images which gives me control over what happens to my work during my lifetime and for 70 years beyond.

There are exceptions which allow copyrighted works to be used for a range of purposes (e.g., private research, current affairs reporting, education or parody) providing what is done to the work is considered ‘fair’.

Access to images online means that all the world can potentially see and steal your photographs. Whilst social media platforms can be asked to ‘takedown’ stolen IP or you can ask the court to issue an interdict, being pro-active and taking preventative steps will hopefully remove the need. I use my watermark symbol on photographs; in this way I am sending out a message that I am IP-aware. Watermarking is a layer of protection that I apply to make photographs harder to steal. This is particularly valuable when posting work online as it otherwise gives unfettered, free access to my work. Further protection can be obtained by inputting copyright information into the metadata of each image.

Should your rights be infringed and you want to enforce copyright, you will need to prove it is your work. In photography this can be achieved by posting regularly on social media and your website and through image metadata, as each image contains a time and date signature.

Territorial copyright exists in most parts of the world and there are an increasing number of copyright registers which act as storage for original work and can be used to verify authorship in the case of a dispute.

When receiving or issuing a commission, copyright lies with the creator. For example, in the video clips below, the photographer has copyright for the imagery, the musician for the soundtrack and the actor for the voice-over. In all cases the person who carries out the commission should state what rights, licenses and permissions the other party has with the work.

Ownership of a trade mark, design or copyright gives you the economic power to sell or transfer the rights of your image(s) for money, either through a license agreement or royalties. Licensing photographs through online stock photography sites such as Adobe Stock, Getty Images or ShutterStock is one possible revenue stream to be considered. These businesses offer a percentage dependent on exclusivity agreements, ranging from 25-50% and some also offer royalties which can be a percentage of gross or net revenue, or a fixed price. In conclusion, whichever approach you take, make sure to do something or you will quickly find your IP being stolen or misused.

Some useful links for additional examples and information:

Scotland Act 1998

Trade Marks Act 1994

Registered Designs Act 1949

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

https://www.newsgroove.co.uk/canon-patents-universal-battery-grip-that-would-fit- multiple-camera-bodies/

https://fsymbols.com/copyright/

https://www.acid.uk.com/about/

Business Law in Scotland book (Green, W.) 4th edition, 2019.

https://hjsolicitors.co.uk/article/top-10-bizarre-intellectual-property-disputes/

https://hjsolicitors.co.uk/article/copyright-and-your-brands-social-media-channels/

https://hjsolicitors.co.uk/article/copyright-infringement-and-takedown-notices/

https://www.acid.uk.com/the-acid-magazine/

https://www.gov.uk/how-to-register-a-trade-mark

https://www.gov.uk/apply-for-a-patent

https://www.gov.uk/register-a-design

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/enforcing-your-copyright

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/intellectual-property-office

https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/handle/10023/9964